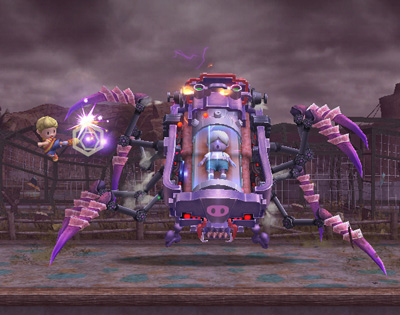

Zelda: Wind Waker HD

The Wii U is still lacking anything resembling a Killer App, and if you don't own one already this is probably not the game to get you to buy one. However, if you do own a Wii U, and you didn't actively hate the original Wind Waker, then the HD version is definitely worth the a play-through. Screenshots aren't going to do it justice; it really looks leaps and bounds better than the original, while still maintaining the charm and vitality that made the first release so memorable. The main changes are visual - brighter colors, more detailed shadows - but the handful of gameplay changes are also welcome, easing some of the repetitiveness that the game was originally criticized for. All in all, I was very happy to get to return to this game, and eagerly, if futilely, await the day when Majora's Mask receives the same treatment.

Oh, that reminds me - the ability to take and share pictures, messages, hints, etc. is actually really cool;. It helps keep the Great Sea from feeling so sparse, gives you something to keep an eye out for on long sea trips (you collect bottles floating on the water or washed up on beaches), and is a neat, if very limited, content generation tool. I'd be psyched to see more stuff like this from Nintendo in the future - useful, but not intrusive, interactivity.

|

| Plus, selfies! |

The Stanley Parable

I tried to write a post about this game awhile back, but realized I had very little to say about it.

There isn't much TO say about The Stanley Parable that doesn't give it away; if you haven't played it I'll just spoil it for you, and if you have played it, you already understand the experience. Certainly it's a funny game, and a clever one, and I enjoyed it. There's very little actual game to be had here, though; skill doesn't play into it at all, and you rarely get any kind of signal ahead of time about what any of your decisions mean, or what they might lead to. This is probably another one of those games that makes us go "Well, what is a game, really?" However, I'm not sure it's asking those questions much better than Soda Drinker Pro did, and Soda Drinker Pro asked with more subtlety (and possibly accidentally). So, play it for a funny, new experience, but if you prod it with too many questions you might find it a little flat.

I tried to write a post about this game awhile back, but realized I had very little to say about it.

There isn't much TO say about The Stanley Parable that doesn't give it away; if you haven't played it I'll just spoil it for you, and if you have played it, you already understand the experience. Certainly it's a funny game, and a clever one, and I enjoyed it. There's very little actual game to be had here, though; skill doesn't play into it at all, and you rarely get any kind of signal ahead of time about what any of your decisions mean, or what they might lead to. This is probably another one of those games that makes us go "Well, what is a game, really?" However, I'm not sure it's asking those questions much better than Soda Drinker Pro did, and Soda Drinker Pro asked with more subtlety (and possibly accidentally). So, play it for a funny, new experience, but if you prod it with too many questions you might find it a little flat.

|

| As an office worker, I also just found it a bit too real, down to the omnipresent, condescending internal narrator. |

Starcraft 2

It surprises me that this game still holds a lot of appeal for me after so long - it is probably to do with the fact that I enjoy watching competitive SC2 so much. Watching streams or tournaments of pro gamers is still a favorite way for my housemate and me to relax; the games remain dynamic, and slight changes take months to manifest themselves in gameplay. The effects of a recent change that slightly reduces the damage of a particular attack are still unrolling, as some players try to adapt their existing playstyle to accommodate the change, and others look for radically different strategies that take advantage of it. As for me, I'm still too afraid to actually go on the ladder, which means a lot of battling against the AI's, but that can only last so long; human opponents are much less predictable, and much more fun, and eventually the fear of losing will be outweighed by my desire to irritate the Gold League by perpetually going mass Swarm Host.

It surprises me that this game still holds a lot of appeal for me after so long - it is probably to do with the fact that I enjoy watching competitive SC2 so much. Watching streams or tournaments of pro gamers is still a favorite way for my housemate and me to relax; the games remain dynamic, and slight changes take months to manifest themselves in gameplay. The effects of a recent change that slightly reduces the damage of a particular attack are still unrolling, as some players try to adapt their existing playstyle to accommodate the change, and others look for radically different strategies that take advantage of it. As for me, I'm still too afraid to actually go on the ladder, which means a lot of battling against the AI's, but that can only last so long; human opponents are much less predictable, and much more fun, and eventually the fear of losing will be outweighed by my desire to irritate the Gold League by perpetually going mass Swarm Host.

Pokémon Y Version

After spending a ridiculous amount of time creating a team to be almost kind-of competitive in the game's most difficult single-player mode - the Battle Maison - I've reached the point I always eventually reach in each Pokémon game, where I realize that I like making a team more than using it. I've always had this issue with Magic: The Gathering as well, where deckbuilding interests me more than actually using a deck. For some reason. I care more about theory, about coming up with a tool that actually works, than in seeing it in practice and negotiating with the chances and risks that make up a game. I'll enjoy a few matches of Pokémon before I start wanting to tweak my team a little more, make a slightly better Dragonite, find a move that gives me slightly better coverage to deal with a particular common enemy. Eventually I find it stops being worth the time investment, so unless I find more people to play with I'll probably shelve it for a little while.

After spending a ridiculous amount of time creating a team to be almost kind-of competitive in the game's most difficult single-player mode - the Battle Maison - I've reached the point I always eventually reach in each Pokémon game, where I realize that I like making a team more than using it. I've always had this issue with Magic: The Gathering as well, where deckbuilding interests me more than actually using a deck. For some reason. I care more about theory, about coming up with a tool that actually works, than in seeing it in practice and negotiating with the chances and risks that make up a game. I'll enjoy a few matches of Pokémon before I start wanting to tweak my team a little more, make a slightly better Dragonite, find a move that gives me slightly better coverage to deal with a particular common enemy. Eventually I find it stops being worth the time investment, so unless I find more people to play with I'll probably shelve it for a little while.

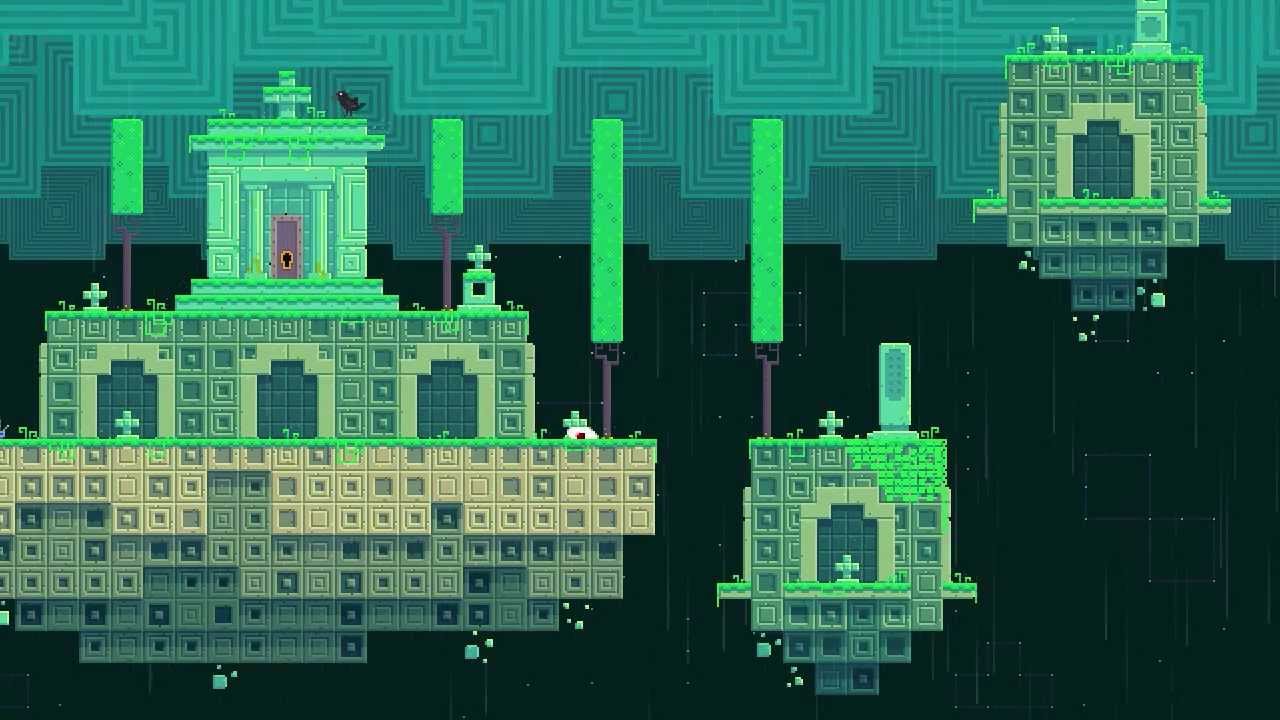

Bastion

I spent only a few minutes on this, and though I'm told I should spend more, I'm having trouble motivating myself for it. Everything I heard about the game before starting was that it looks beautiful and has one of the best soundtracks in games, and so far that's borne out. However, the core gameplay underneath it hasn't been enough to keep hold of me. I've never really into these kinds of click-and-run games - they remind me too much of Diablo II, which I've played too much of in my life.

I may go back to it after I get through Journey, Heavy Rain, and Assassin's Creed IV; we'll see how that goes.

I spent only a few minutes on this, and though I'm told I should spend more, I'm having trouble motivating myself for it. Everything I heard about the game before starting was that it looks beautiful and has one of the best soundtracks in games, and so far that's borne out. However, the core gameplay underneath it hasn't been enough to keep hold of me. I've never really into these kinds of click-and-run games - they remind me too much of Diablo II, which I've played too much of in my life.

|

| It IS quite pretty, though. |

I may go back to it after I get through Journey, Heavy Rain, and Assassin's Creed IV; we'll see how that goes.