Hi!

For those who haven't noticed, I'll be taking this week off - visiting family and generally relaxing a bit. I'll be back with more biting witticisms and incisive commentary on Tuesday.

Enjoy the holidays!

(Subheader)

Updates Tuesdays and Fridays.

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Friday, November 22, 2013

Game Day: Soda Drinker Pro

This won't be a long post. Soda Drinker Pro is a really weird game and to enjoy it you have to be in a particular mood, or have a particular sense of humor, or enjoy questioning stuff for no real reason and without any real hope of answers. Preferably, all three.

In this stirring title - which I was fortunate enough to get to see in a booth at Boston FIG earlier this year - you control a nameless everyman, exploring landscapes rendered in almost-unequaled beauty with a soda in hand at a snail's pace, to better enjoy your surroundings and soda. At any time, you may take a sip of your soda - or not, at your decision! As you drink, your Soda Meter slowly depletes, until the whole soda is consumed. But not to worry! You will immediately receive a new soda and be transported to a new level besides!

As you wander, you find yourself confronting questions that normally we can dodge in day-to-day life. Where am I? What of perception is real, and what is merely spraypainted onto boxes surrounding me to create the illusion of reality? What world exists after this one? Where do we go when we finish our sodas? Why am I moving so slowly? Should I drink soda now? What about now? Maybe now? Now that I'm drinking soda, should I stop? As you ask yourself these questions, your avatar will make comments about his surroundings, and the soda you are drinking there.

This continues for 100+ levels.

I can see three possible reactions to this:

1) Decide that this is all incredibly stupid, and ignore it entirely;

2) Decide it sounds kind of funny and play it for as long as the humor lasts;

3) Treat it like an actual art object worthy of attention and critical consideration.

Is Soda Drinker Pro actually intended as art? Maybe to probably not, but to a person who likes overanalysis as much as I do, it does pose some interesting questions. Why the hell does this game exist? Why are we playing it? For that matter, why are we playing ANY game, when so many of them amount to something similar - walk around a static environment and push a couple buttons to win? What distances Soda Drinker Pro from those other games? The game itself doesn't offer much in the way of answers, but if you enjoy asking them, or if you enjoy simulated soda drinking, it has a lot to give to you anyway. Personally I find it pretty funny that, among so many games trying to be art and so many people asking questions about games as art, this game can be so casually uninterested in those questions and still do such a good job of making me ask them.

And, yeah, for the record it IS the very best first person soda simulator you are ever going to play.

|

| Pictured: Art. |

In this stirring title - which I was fortunate enough to get to see in a booth at Boston FIG earlier this year - you control a nameless everyman, exploring landscapes rendered in almost-unequaled beauty with a soda in hand at a snail's pace, to better enjoy your surroundings and soda. At any time, you may take a sip of your soda - or not, at your decision! As you drink, your Soda Meter slowly depletes, until the whole soda is consumed. But not to worry! You will immediately receive a new soda and be transported to a new level besides!

As you wander, you find yourself confronting questions that normally we can dodge in day-to-day life. Where am I? What of perception is real, and what is merely spraypainted onto boxes surrounding me to create the illusion of reality? What world exists after this one? Where do we go when we finish our sodas? Why am I moving so slowly? Should I drink soda now? What about now? Maybe now? Now that I'm drinking soda, should I stop? As you ask yourself these questions, your avatar will make comments about his surroundings, and the soda you are drinking there.

This continues for 100+ levels.

I can see three possible reactions to this:

1) Decide that this is all incredibly stupid, and ignore it entirely;

2) Decide it sounds kind of funny and play it for as long as the humor lasts;

3) Treat it like an actual art object worthy of attention and critical consideration.

Is Soda Drinker Pro actually intended as art? Maybe to probably not, but to a person who likes overanalysis as much as I do, it does pose some interesting questions. Why the hell does this game exist? Why are we playing it? For that matter, why are we playing ANY game, when so many of them amount to something similar - walk around a static environment and push a couple buttons to win? What distances Soda Drinker Pro from those other games? The game itself doesn't offer much in the way of answers, but if you enjoy asking them, or if you enjoy simulated soda drinking, it has a lot to give to you anyway. Personally I find it pretty funny that, among so many games trying to be art and so many people asking questions about games as art, this game can be so casually uninterested in those questions and still do such a good job of making me ask them.

And, yeah, for the record it IS the very best first person soda simulator you are ever going to play.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

Demo Night Lessons: Criticism

The Boston Indies meetup happened yesterday, and it was demo night, so Andrew and I brought a couple of laptops and a couple of burritos and set into full BostonFIG-style "Play our game!" mode, and it was totally awesome.

One of the best things about the Boston Indies is that it's full of indie game developers, many of whom do what I do, except they do it for a living, and it's intimidating as hell to put our game in front of them, and next to their games. But we did, and I wanted to talk just briefly about what we learned and what it makes me think of.

We put this game in front of a lot of people last night and got a ton of really useful feedback. Nobody had only negative things to say, at least to our faces. Even the people with criticisms phrased them in a helpful way, and included positive things on either side, compliment sandwich-style, and generally went way far out of their way to be kinder than they had to be. That said: the negative comments did hurt a bit, and they're the parts that I've been mulling over constantly since I heard them.

The most frequent or most troublesome feedback we got was:

-Not enough of a sense of progress through the level

-Not enough narrative/driving force

-Jumping feels "floaty"/platforming elements feel imprecise in general

-Animation is obviously rough, esp. in contrast with more refined features

-Some puzzles seem more like guesswork than like solving

And, the strangest thing I heard,

-Characters are unusually tall and slender for a platformer

Some of these criticisms don't really hurt (I don't mind that the animation is bad, it's a stand-in and I made it myself with no animation experience), some are frustrating truths but things I already knew (jumping is floaty despite hours of messing around with it, but we know it needs to be fixed), and some are things I feared and was saddened to have confirmed (a "puzzle" I spent a long time on isn't really that puzzley or fun). All of them were useful because they indicated what stood out to experienced players and developers, and told us what we need to sharpen.

In any creative medium, criticism is an incredibly tricky thing to deal with. It takes a lot of energy to pour hours of your life into a project you care about deeply. It takes even more energy to share that meaningful project with others, flaws and all. And it can be pretty tough to stand there while those flaws are listed out and to see it not as a tear-down of what you've so carefully sculpted but as advice on where to chisel next. So, yeah, unfortunately it can be kind of painful to have your project dissected and have people pointing out everything wrong with it, but it's also probably the single most important part of revising your piece into something worthwhile. If you're making your art for anybody but yourself - to share, to give, to sell, to show - you'll want to refine it not just against your own preferences, but those of as many people as you can convince to look at it.

So, with that in mind, this is a cycle I've found to be helpful in accruing feedback:

-Pick something to work on. If you're making a game, this might be as simple as a mechanic or as big as a level; it might be a paragraph of a story or a chapter, a sketch or a painting. Decide what it is you want to do, and set your scale small enough that you don't mind revising or redoing a lot of it.

-Come up with an idea of what you want it to be. This is in general just an important step of design - figure out what it should be before you start messing with it. Sometimes art arrived at organically without much forethought is great - it's not the norm, though. Planning will save you a lot of time in revision and help give you a clearer idea when you're done of what to improve. Include others in brainstorming if it's helpful.

-Work on it until you get stuck, or until you think it can't be improved. If you get to a place where you think what you've made is perfect, you're wrong; this is one of the best times to seek outside input because you'll be getting help for problems you weren't aware existed. That said, don't spend forever honing something to "perfection" before getting an outside view; show it to people along the way, especially when you see a need for improvement but aren't sure how to go about it.

-Find someone (or a group of someones) who will give you precise, honest criticism of the piece. It's definitely nice getting praise, but for this step you need someone who isn't afraid to hurt your feelings. Boston FIG was great for us because we got a lot of praise, which told us that Candlelight was worth making; at the same time, it didn't really inform the creative process much. You want somebody who cares about what you're doing enough that they'll wound your pride, badly if necessary, to make your piece into the best it can be.

-Listen carefully and do not talk. Don't offer defenses, excuses, or apologies; don't tell people you knew about the issue they're describing; don't do anything but take earnest notes on what they've noticed. Even if you think you know it already, write it down - it matters that the flaw is big enough to be seen both by someone as close to the project as you, and someone as far from it as your critic. I am very bad at anything requiring me not to talk, and this is no exception. At this stage you need to separate yourself from the work; it doesn't matter how it got to the state it's in or why you let it get there, what matters is how it's going to improve from where it is.

-Identify problems. I mentioned earlier that someone said my characters were the wrong shape for a platformer. I took note of this, but didn't bother to ask why they're the wrong shape - that is, what problem their shape creates, and how changing it would solve that problem. This phase is very, very important. If someone tells you "Oh, you should do X" and you do it blindly, you might not solve the problem they're trying to address, or create new problems, or simply compromise your vision of the project. Find a clear way to actually state the problem underlying their criticism or advice - this is what you need to address.

-Repeat. Great! You've found things that need improving! Go improve them, then bring them back up for inspection. You won't solve every problem this way, and you won't please everyone, but neither is the goal. The goal is to create the best product you can within the limits of your abilities, resources, and vision - all of which will be expanded by this revision process.

Throughout this process, it is important to seek out positive feedback as well. Unless you're unnaturally gratified by getting your work criticized, the whole process can start to wear on you. It helps, a lot, to have people reassure you that you're producing something good, that the block of stone you're sculpting still has a masterpiece somewhere in it and you've managed to identify some of those contours. The more of your mistakes you can identify, the more you can learn to correct them, and the better your art will be for it.

I'm going to go try to find a way to make sure my characters don't keep smacking their heads on ceilings when they jump. Wish me luck.

One of the best things about the Boston Indies is that it's full of indie game developers, many of whom do what I do, except they do it for a living, and it's intimidating as hell to put our game in front of them, and next to their games. But we did, and I wanted to talk just briefly about what we learned and what it makes me think of.

We put this game in front of a lot of people last night and got a ton of really useful feedback. Nobody had only negative things to say, at least to our faces. Even the people with criticisms phrased them in a helpful way, and included positive things on either side, compliment sandwich-style, and generally went way far out of their way to be kinder than they had to be. That said: the negative comments did hurt a bit, and they're the parts that I've been mulling over constantly since I heard them.

The most frequent or most troublesome feedback we got was:

-Not enough of a sense of progress through the level

-Not enough narrative/driving force

-Jumping feels "floaty"/platforming elements feel imprecise in general

-Animation is obviously rough, esp. in contrast with more refined features

-Some puzzles seem more like guesswork than like solving

And, the strangest thing I heard,

-Characters are unusually tall and slender for a platformer

Some of these criticisms don't really hurt (I don't mind that the animation is bad, it's a stand-in and I made it myself with no animation experience), some are frustrating truths but things I already knew (jumping is floaty despite hours of messing around with it, but we know it needs to be fixed), and some are things I feared and was saddened to have confirmed (a "puzzle" I spent a long time on isn't really that puzzley or fun). All of them were useful because they indicated what stood out to experienced players and developers, and told us what we need to sharpen.

In any creative medium, criticism is an incredibly tricky thing to deal with. It takes a lot of energy to pour hours of your life into a project you care about deeply. It takes even more energy to share that meaningful project with others, flaws and all. And it can be pretty tough to stand there while those flaws are listed out and to see it not as a tear-down of what you've so carefully sculpted but as advice on where to chisel next. So, yeah, unfortunately it can be kind of painful to have your project dissected and have people pointing out everything wrong with it, but it's also probably the single most important part of revising your piece into something worthwhile. If you're making your art for anybody but yourself - to share, to give, to sell, to show - you'll want to refine it not just against your own preferences, but those of as many people as you can convince to look at it.

So, with that in mind, this is a cycle I've found to be helpful in accruing feedback:

-Pick something to work on. If you're making a game, this might be as simple as a mechanic or as big as a level; it might be a paragraph of a story or a chapter, a sketch or a painting. Decide what it is you want to do, and set your scale small enough that you don't mind revising or redoing a lot of it.

-Come up with an idea of what you want it to be. This is in general just an important step of design - figure out what it should be before you start messing with it. Sometimes art arrived at organically without much forethought is great - it's not the norm, though. Planning will save you a lot of time in revision and help give you a clearer idea when you're done of what to improve. Include others in brainstorming if it's helpful.

-Work on it until you get stuck, or until you think it can't be improved. If you get to a place where you think what you've made is perfect, you're wrong; this is one of the best times to seek outside input because you'll be getting help for problems you weren't aware existed. That said, don't spend forever honing something to "perfection" before getting an outside view; show it to people along the way, especially when you see a need for improvement but aren't sure how to go about it.

-Find someone (or a group of someones) who will give you precise, honest criticism of the piece. It's definitely nice getting praise, but for this step you need someone who isn't afraid to hurt your feelings. Boston FIG was great for us because we got a lot of praise, which told us that Candlelight was worth making; at the same time, it didn't really inform the creative process much. You want somebody who cares about what you're doing enough that they'll wound your pride, badly if necessary, to make your piece into the best it can be.

-Listen carefully and do not talk. Don't offer defenses, excuses, or apologies; don't tell people you knew about the issue they're describing; don't do anything but take earnest notes on what they've noticed. Even if you think you know it already, write it down - it matters that the flaw is big enough to be seen both by someone as close to the project as you, and someone as far from it as your critic. I am very bad at anything requiring me not to talk, and this is no exception. At this stage you need to separate yourself from the work; it doesn't matter how it got to the state it's in or why you let it get there, what matters is how it's going to improve from where it is.

-Identify problems. I mentioned earlier that someone said my characters were the wrong shape for a platformer. I took note of this, but didn't bother to ask why they're the wrong shape - that is, what problem their shape creates, and how changing it would solve that problem. This phase is very, very important. If someone tells you "Oh, you should do X" and you do it blindly, you might not solve the problem they're trying to address, or create new problems, or simply compromise your vision of the project. Find a clear way to actually state the problem underlying their criticism or advice - this is what you need to address.

-Repeat. Great! You've found things that need improving! Go improve them, then bring them back up for inspection. You won't solve every problem this way, and you won't please everyone, but neither is the goal. The goal is to create the best product you can within the limits of your abilities, resources, and vision - all of which will be expanded by this revision process.

Throughout this process, it is important to seek out positive feedback as well. Unless you're unnaturally gratified by getting your work criticized, the whole process can start to wear on you. It helps, a lot, to have people reassure you that you're producing something good, that the block of stone you're sculpting still has a masterpiece somewhere in it and you've managed to identify some of those contours. The more of your mistakes you can identify, the more you can learn to correct them, and the better your art will be for it.

I'm going to go try to find a way to make sure my characters don't keep smacking their heads on ceilings when they jump. Wish me luck.

Saturday, November 16, 2013

Game Day: Neocolonialism

Why, yes, Boston does have a thriving independent game dev community, full of excellent people making excellent games . This particular game I've been curious about since I first heard about it at the start of the year, and since its release was earlier this month I'd like to share my experience with it.

Neocolonialism is about unabashedly being a bastard in a way that's smarter and more topical than any other recent game seeking smart and topical.

As the head of a multinational corporation, you use your clout to buy parliamentary votes in countries worldwide. These votes let you elect prime ministers from among the players, who in turn present proposals for the parliament to vote for. Collectively, you'll propose and ratify mines and factories, set up free trade agreements, intervene in international crises, and build up your political power, letting you buy more parliamentary votes in other countries, slowly bleeding the world dry. After twelve turns of this, the game ends; before then, you'll want to liquidate as many of your parliamentary votes as you can, funneling the money into your Swiss bank account. Whoever's account is flushest at the end of the game is the winner, triumphant amid the ruin of the rest of the planet.

The play itself is simple, with a few choices spiraling out into a lot of possibility and nuance. Each turn has three parts. In the investment phase, players taking turns buying or selling parliamentary votes around the world until no player can or wants to make another move. In the policy phase, players vote on issues in each region in turn, and if they're the prime minister of that region, they can make proposals, including mines, factories, and free trade agreements, that affect the value of votes in that (and possibly other) regions. Because multiple players may benefit from a region, and no player collects income on a region if it has no prime minister, it's sometimes in your interest to cede power to another - especially if you can set up a shady backroom deal with them over it. In the IMF (International Monetary Fund) phase, some national crisis - a strike, a collapse - occurs in a region, possibly changing the value of resources in that country. Each turn, one player gets to decide what intervention, if any, should take place there. This can ruin strategies or open up new ones if you're clever enough to find them.

I'll admit that I haven't had a chance to play against actual humans - I've only gotten to play against AI opponents with names like Thatcher and Reagan, whose policies the game is an obvious parody of. That said, it's a lot of fun - there are a lot of different strategies to take, a lot of different ways to conspire with and against the other players. The tutorials are a little dense, but helpful for the uninitiated - once you're through them, you'll have enough to play a game or two and get the hang of things. At first it just seems like getting as much income as possible, but by the end of the game, when there's a lot of money to throw around and not that many votes left to buy, you'll wish you'd cashed out some parliamentary votes a little earlier - just don't make the mistake I did of selling too much too early and watching in horror as the other players swallowed up the free votes I left behind. Even once you hammer out a strategy you can still get thrown for a loop if some unexpected disaster blows a hole in one of your investments. There's a lot to account for, but when things work out it's immensely satisfying to burn through all your votes on the last turn and watch your bank account fill up.

So far my favorite thing is the deadpan sense of humor combined with incisive politics. It's a clever presentation of insidious policy that is, unfortunately, all too real across regular, right-side-up maps. It's not just "corporations have too much influence;" it's "the policies of money infiltrate, manipulate, and ruin more nations than the ones where they originate." It's a statement not only about how we screw ourselves with our financial and electoral decisions, but about how we screw everybody with those decisions, which is a much less comfortable truth. It's not being said loudly enough in any medium, and seeing such an excellent representative in video games, which are often behind the times on social issues, is satisfying as hell.

In summary: Support it because it's important, play it because it's fun.

Subaltern Games website: http://subalterngames.com/

Neocolonialism is about unabashedly being a bastard in a way that's smarter and more topical than any other recent game seeking smart and topical.

|

| But you're ruining everything in a way that benefits you so it's ok. |

As the head of a multinational corporation, you use your clout to buy parliamentary votes in countries worldwide. These votes let you elect prime ministers from among the players, who in turn present proposals for the parliament to vote for. Collectively, you'll propose and ratify mines and factories, set up free trade agreements, intervene in international crises, and build up your political power, letting you buy more parliamentary votes in other countries, slowly bleeding the world dry. After twelve turns of this, the game ends; before then, you'll want to liquidate as many of your parliamentary votes as you can, funneling the money into your Swiss bank account. Whoever's account is flushest at the end of the game is the winner, triumphant amid the ruin of the rest of the planet.

The play itself is simple, with a few choices spiraling out into a lot of possibility and nuance. Each turn has three parts. In the investment phase, players taking turns buying or selling parliamentary votes around the world until no player can or wants to make another move. In the policy phase, players vote on issues in each region in turn, and if they're the prime minister of that region, they can make proposals, including mines, factories, and free trade agreements, that affect the value of votes in that (and possibly other) regions. Because multiple players may benefit from a region, and no player collects income on a region if it has no prime minister, it's sometimes in your interest to cede power to another - especially if you can set up a shady backroom deal with them over it. In the IMF (International Monetary Fund) phase, some national crisis - a strike, a collapse - occurs in a region, possibly changing the value of resources in that country. Each turn, one player gets to decide what intervention, if any, should take place there. This can ruin strategies or open up new ones if you're clever enough to find them.

|

| The map is upside-down. |

|

| Help or hinder another player for personal gain, to set a trap, to strike a deal, or because why the hell not? |

In summary: Support it because it's important, play it because it's fun.

Subaltern Games website: http://subalterngames.com/

Tuesday, November 12, 2013

The Art of Game Design

When I started designing Candlelight I asked for resources on game design to get started, and someone directed me towards The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, by Jesse Schell. This book does not contain instructions on what programs to make your game in. It does not teach you how to code. It does not tell you which market to strive for. It is, however, the most important $40 I have spent on Candlelight, and some of the best money I've ever spent in my life, and it's time I gave it the due it deserves here.

The Art of Game Design contains the word "Art" in its title for a reason: its focus is on the craft, on the process, of creating a refined game. In any art, there are certain physical tools - paints, clays, cameras, etc. - that are required for success. However, these are not the substance of the art itself, and simply understanding them is insufficient to produce great works. Schell recognizes this; though he does spend time addressing the tools and technologies of game design, much of the book focuses on the intangibles of design. Art is difficult to teach, and game design is no different. Schell offers frameworks and rules for practicing game design, which the student can use to hone their mastery of the craft.

These frameworks come in the form of 100 lenses presented gradually throughout the book. Each lens offers a way of looking at the game for the sake of refining it. For example, the lens of Flow asks the designer to look at the player's skills and how they develop as the player pursues goals; the lens of Accessibility asks the designer to look at how easy the game and its challenges are to understand to a newcomer; and the lens of the Raven asks the gamer to only focus on what's important by constantly asking "Is this worth my time?" Schell posits early that the game isn't merely its game board, or dice, or installer package; it's an experience, shaped by the designer, explored by the player, and influenced by a hundred other factors besides. The book slowly draws a map of that experience, and the factors the designer must consider when constructing their experience for the player.

What I personally enjoyed so much about this book, however, was that it was not only useful for me as a game developer but also expanded my view of the world in general. Schell's discussions of art, psychology, people, architecture, and dozens of other subjects are certainly all presented with game development in mind, but are also useful more generally. In attempting to grant enough perspective on a subject to use it to design games, Schell does an excellent job of quickly illustrating the salient points of the subject in a way that I found eye-opening and very enjoyable. The book would have been worthwhile without such moments, but the frequency of these moments are what make it an exceptional read.

The Art of Game Design is as general as possible, and can be applied to games of any type, from simple card games to MMO's. Obviously not all of the content is applicable to every game, but there's plenty to be had regardless of the experience you hope to produce. Even non-developers with an interest in games will find much of value here; if nothing else, it can do a lot to develop the skills of anyone looking to analyze games critically.

I don't know Jesse Schell and nobody is paying me to endorse this book; I sincerely think it's amazing enough to warrant my spending the time telling you about it, and I hope you look into it and pick up a copy if it's at all up your alley.

Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/The-Art-Game-Design-lenses/dp/0123694965

Website: http://artofgamedesign.com/book/

These frameworks come in the form of 100 lenses presented gradually throughout the book. Each lens offers a way of looking at the game for the sake of refining it. For example, the lens of Flow asks the designer to look at the player's skills and how they develop as the player pursues goals; the lens of Accessibility asks the designer to look at how easy the game and its challenges are to understand to a newcomer; and the lens of the Raven asks the gamer to only focus on what's important by constantly asking "Is this worth my time?" Schell posits early that the game isn't merely its game board, or dice, or installer package; it's an experience, shaped by the designer, explored by the player, and influenced by a hundred other factors besides. The book slowly draws a map of that experience, and the factors the designer must consider when constructing their experience for the player.

What I personally enjoyed so much about this book, however, was that it was not only useful for me as a game developer but also expanded my view of the world in general. Schell's discussions of art, psychology, people, architecture, and dozens of other subjects are certainly all presented with game development in mind, but are also useful more generally. In attempting to grant enough perspective on a subject to use it to design games, Schell does an excellent job of quickly illustrating the salient points of the subject in a way that I found eye-opening and very enjoyable. The book would have been worthwhile without such moments, but the frequency of these moments are what make it an exceptional read.

The Art of Game Design is as general as possible, and can be applied to games of any type, from simple card games to MMO's. Obviously not all of the content is applicable to every game, but there's plenty to be had regardless of the experience you hope to produce. Even non-developers with an interest in games will find much of value here; if nothing else, it can do a lot to develop the skills of anyone looking to analyze games critically.

I don't know Jesse Schell and nobody is paying me to endorse this book; I sincerely think it's amazing enough to warrant my spending the time telling you about it, and I hope you look into it and pick up a copy if it's at all up your alley.

Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/The-Art-Game-Design-lenses/dp/0123694965

Website: http://artofgamedesign.com/book/

Thursday, November 7, 2013

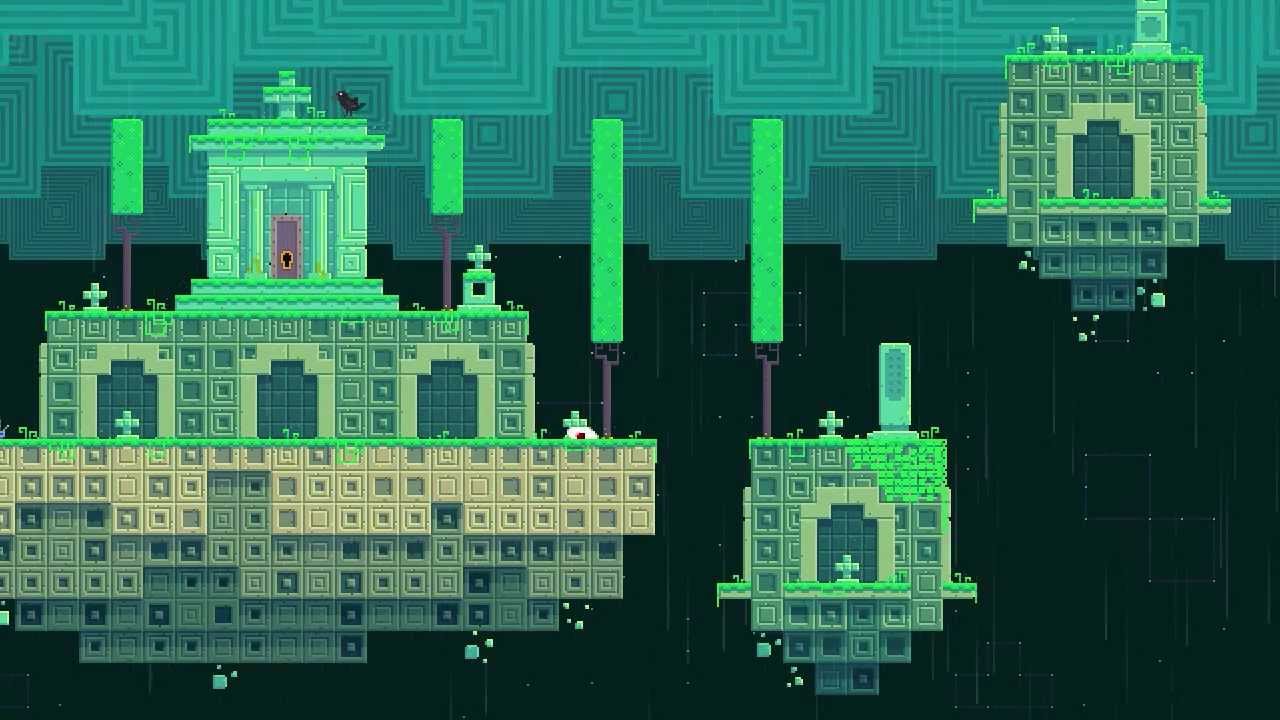

FEZ

|

| Pictured: Only part of the picture. |

Armed with this ability, you'll proceed through a maze of non-linear levels, collecting cubes that can be used to open doors to new areas. The cubes are usually either out of reach, requiring tricky rotating to access, or hidden by puzzles ranging in difficulty from "cute" to "absolutely diabolical." You'll be accompanied by a tesseract-shaped sprite who's a bit like Navi but less helpful and more annoying - it's part of the charm.

I'll get the "review" part out of the way quickly; it's well-written, well-scored, beautiful, clever, and an excellent use of your time if you're at all into puzzle games. Go play it.

So! Particulars. The two things I like best about the game are the incredible amount of emergent puzzles that appear out of its simple mechanics, and the open-world exploration mentioned in the previous post.

The ability to rotate the world is one of those mechanics that can make anyone with a trained eye for development drool. It's simple to use, its implications are subtle, and its uses continually unfold throughout the game in a series of incredibly satisfying discoveries. You might be climbing up a ladder, and rotate the screen so that your ladder segment lines up with a more distant one, allowing you to climb further - except that you rotate yourself into a glitch and die (which is a nuisance but not a major setback). You can grab hold of a lever and rotate the screen to rotate a piece of the level with you, relative to the rest of the screen. Some levels impose additional restrictions on you, or offer you a couple toys to play with, but the core of the mechanics never change - you just discover new ways to use them.

|

| You can also just hang out by this lighthouse indefinitely. It's a pretty good lighthouse. |

|

| There's a lot of game here, and it's all fantastic. |

The game can get a little frustrating in places, and if you're impatient it can definitely be tempting to throw up your hands at the more complicated puzzles. But push past it! If you miss being challenged by puzzles and love to explore and map out the secrets of a world, you'll get pulled in immediately - and it's a pretty great game to get pulled into.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Freedom in games - World space

I've been talking a lot with a friend recently about what makes games fun, or what makes the kinds of stories they tell different from other stories, or what the ideal "Gaminess" of a game might look like - and how many lack it. This is an interesting discussion but also kind of a headache; I'd like to come at this problem sideways, maybe over the course of a few posts.

One thing, maybe the main thing, that makes a game different from other media is choice on the part of the audience. This, too, is kind of a big topic - choice in games is about risk, reward, consequence, and discovery. So we'll break that down further, into the kinds of freedoms a player is afforded: the kinds of choices they can make. And I'll go ahead and narrow it down even more. So! Today we're going to be talking about choice and player freedom as a function of the world - the space the player's virtual avatar occupies in a game.

|

| Words. |

World space and freedom are pretty strongly linked in the mind of many players. Most of what we think of as "Sandbox games" are games with large worlds that don't restrict your travel, allowing you to use all the actions of your character anywhere in a large gamespace, and limiting your travel between parts of the gamespace in relatively few ways. The best recent example is Skyrim, where, upon completing the game's introduction, you're free to more or less go anywhere in the world and do whatever you like. So, when we think of a space as offering freedom, we tend to think of that space as:

-Large

-Non-linear

This doesn't need to hold in every space within the game - dungeons in Skyrim are usually quite linear, with relatively little exploration - but if the world, the highest-level gamespace, has these qualities, we tend to feel that we've been given freedom in that game.

In all gameplay elements, freedom is about finding a balance between too little and too much freedom. When a game space fails at providing freedom, it is because moving through the game space no longer feels meaningful. If our choices about exploring a space are very few - we can move forward, but not backward, through world 1-1 in Super Mario Bros., and can jump along the way - this won't necessarily make us feel constricted. However, it limits the developer's ability to use space as a means of granting the players freedom. (This particular game has a powerful counterexample in world 1-2, where you can jump up above the top of the level to bypass the level's hazards and reach a special warp zone to take you later in the game - in this case, the earlier limitations imposed cause this moment to feel intensely freeing/gratifying.)

|

| We all felt so clever the first time we figured this out. |

Conversely, if we have many opportunities to explore, but little reason to go one way or another, the player can lose interest; if there's no evident advantage to going one way or another, players start to wonder why they're exploring at all. FEZ, for all its delightfulness, feels this way a little bit at the beginning; with a vast web of rooms to explore, and little benefit to selecting one over another (each one containing mostly self-contained puzzles and rewarding you with the keys needed to unlock other areas), it's hard to know why you're going in any particular direction.

|

| Don't worry, we'll come back to the stuff FEZ does right with space in a minute. |

As a game world gets bigger, the requirement that choices be meaningful becomes weightier; if you're going down one path instead of any of seven others - each of which has its own four paths away from it - you're going to want to feel like your choice served some purpose, and preferably that it was distinct in meaningful ways from the other choices.

The right amount of freedom in space is incredibly local to the specific game experience. Some games don't need much; like Super Mario Bros., they're not interested in using game space to create a sense of freedom. Half-Life creates a game space that's large and feels natural, but whose linearity and cramped quarters limit freedom in a way that contributes to its horror atmosphere. Some games need to vary the amount of freedom based on the part of the game you're in; Wind Waker's dungeons, which are fairly linear and directly goal-oriented, create a more challenging contrast to the free sailing that takes up much of the game.

Wind Waker and Skyrim are both games that afford the player a great deal of freedom. To keep this freedom from being paralyzing, they both:

-Make the player's path clear, so a player pursuing the a particular objective doesn't get lost in the vast world;

-Make side objectives and exploration rewarding enough to feel meaningful and worthwhile

In combination, these aspects create worlds that seem larger than they are because at any point, the player can detour from their primary objective, go on some side adventures, and easily pick up the main thread again, usually better off for their dallying. In Wind Waker and Skyrim, this creates an enormous feeling of freedom and helps the world feel huge, continuous, and immersive. FEZ, meanwhile, never gives you a path through its world that's especially clear. However, whatever path you choose allows for progress, and ultimately all or most of the game must be explored, so choices made rarely feel frustrated. Combined with the fact that the game is gorgeous, and exploring and learning about the world is a puzzle unto itself, FEZ turns the wandering exploration into its own reward, letting you slowly discover and claim the various levels.

So! If you want to have a big, open game, you've got to find a way to structure it such that players never feel lost, and always feel like there's meaning in the decisions they make about where they go. If you've got a narrow, linear game, then you don't have to think about it as much! It does mean you need to find other ways to keep your game engaging, though. Used improperly, open space and freedom of movement muddies the experience and makes your game feel overambitious or padded or simply boring; used correctly, it can create a lush, memorable world that acts as a backdrop for emergent stories players write themselves.

|

| In which we could be any-damn-where. |

-Make the player's path clear, so a player pursuing the a particular objective doesn't get lost in the vast world;

-Make side objectives and exploration rewarding enough to feel meaningful and worthwhile

In combination, these aspects create worlds that seem larger than they are because at any point, the player can detour from their primary objective, go on some side adventures, and easily pick up the main thread again, usually better off for their dallying. In Wind Waker and Skyrim, this creates an enormous feeling of freedom and helps the world feel huge, continuous, and immersive. FEZ, meanwhile, never gives you a path through its world that's especially clear. However, whatever path you choose allows for progress, and ultimately all or most of the game must be explored, so choices made rarely feel frustrated. Combined with the fact that the game is gorgeous, and exploring and learning about the world is a puzzle unto itself, FEZ turns the wandering exploration into its own reward, letting you slowly discover and claim the various levels.

|

| Owls creep me out. |

|

| Here the player controlling the ball gets to explore an exciting world of numbers, lines, and other lines. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)